How we Compare Strikes for Selling Puts

Today we’re going to walk through how we compare strikes for selling puts. When we sell a put option contract we only sell them on companies we want to own, and only at the price we’re happy to own the company at. For example, we might have a company we really want to own and we want to own it for $35 per share or less. If it’s trading at $60 and we want to sell to open the $35 strike, we’d be lucky to fill that contract at all because the trading price is so far from the strike price. If it’s trading at $45 we might be able to sell a put contract for the $35 strike, but likely not for enough premium to make it worthwhile. What’s worthwhile?

When we sell to open a put option contract we’re making a promise to buy the company at that strike price between now and the expiration date of the contract. So using the $35 strike price example, we’re putting up $3,500 for each put option contract we sell. We won’t have access to that capital again until the contract expires. So in effect we’re tying up that capital, and we want to get a decent return on it. For that to happen, the trading price needs to be near, but not necessarily on top of, our strike price.

So if a company we like at $35 is trading for $60, we’ll just watch the company and wait for something to happen that causes the trading price to drop. When it gets to around $40 per share then we’ll start selling puts at the $35 strike, as long as we can get enough premium for it to make sense.

So how much premium makes sense?

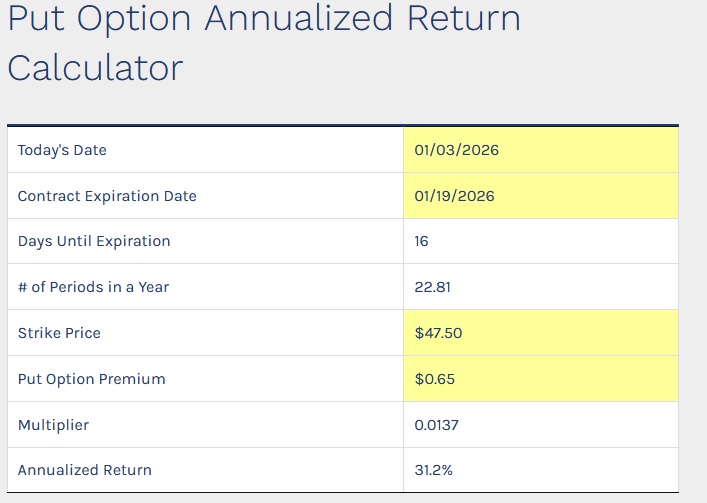

When we compare strikes for selling puts we target a 20% annualized return. So we look at both the premium and the number of days until expiration. Let’s say the company only has monthly options. In that case the contract expires the third Friday of the next month and the trade will be active for one month in total. There are twelve months in a year, so we could theoretically do this trade twelve times over the course of a year. That makes our time multiplier 12.

Then we look at the strike. When we’re entering a position in a company we’ll pick a strike that is a little below the current trading price. If we already have shares we’ll aim for a floor between our strike and the current trading price. If we don’t have shares yet then we want to be a little closer to the money so make it more likely we get shares. For example, we have a company that’s trading at $40 and there are strikes at $35 and $37.50. We have a few shares right now and are happy to buy more. In that case we’re likely to look at the $37.50 strike. If we have lots of shares and are looking to fill our fourth or fifth tranche, then we’ll look more at the $35 strike.

When we compare strikes for selling puts we also factor in the premium. The $37.50 strike is giving $0.90 in premium while the $35 strike is giving $0.30. Let’s compare those two. We take the premium (what we’ll be paid) and divide it into the strike price (what we’ll be risking). So for the $37.50 strike we divide $0.90 into $37.50 and we get 0.024. Then we multiply that by our time multiplier and we get 0.288. That’s an annualized return of 28.8% on the $3,750 we’re putting up to make this trade. That’s solid.

Now let’s look at the $35 strike. We take the $0.30 in premium and divide that into the $35 strike. That gives us 0.0086. Then we multiply that by our time multiplier which is 12. That gives us 0.103. That’s an annualized return of 10.3%. Better than a savings account, but we can do better. Our Stock Option Annualized Return Calculator helps with that math. By using the same calculation we’re able to objectively compare strikes for selling puts.

Remember, we’re only selling puts on a company we want to own at the strike price we sell. We’re also factoring in how many shares of the company we already have. If we don’t have many shares we’ll be more aggressive on our put strikes. We also look at floors in the trading price to help us choose.